As of October 25 at the Kunsthalle München

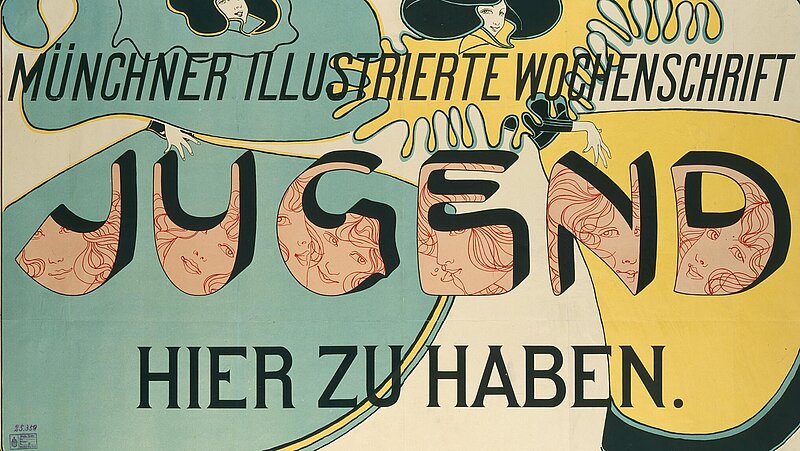

Around 1900, young visionary artists in Munich set out to revolutionize art and to reform life. Facing a time of rapid scientific as well as technical innovation and social upheaval, they joined the quest for a fairer and more sustainable way of life. Artists such as Richard Riemerschmid, Hermann Obrist, and Margarethe von Brauchitsch turned their backs on historical styles to create a new art that permeated life down to the smallest detail. Their ideas formed the foundation for modern art and design. With examples from painting, graphic art, sculpture, photography, decorative arts, and fashion, the exhibition sheds light on Munich’s role as the cradle of Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) in Germany and demonstrates how topical the issues of life discussed back then still are today.

The exhibition is a joint project of the Kunsthalle München and the Münchner Stadtmuseum.

Plan Your Visit

Opening hours

Although the Münchner Stadtmuseum's exhibitions closed on January 8, 2024, for a complete renovation, the cinema and the Stadtcafé will remain open to visitors until June 2027.

Information to Von Parish Costume Library in Nymphenburg

Filmmuseum München – Screenings

Tuesday / Wednesday 6.30 pm and 9 pm

Thursday 7 pm

Friday / Saturday 6 pm and 9 pm

Sunday 6 pm

Contact

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1

80331 München

Phone +49-(0)89-233-22370

Fax +49-(0)89-233-25033

E-Mail stadtmuseum(at)muenchen.de

E-Mail filmmuseum(at)muenchen.de

Ticket reservation Phone +49-(0)89-233-24150