Eisner misjudges the situation

As a member of the SPD, he relies on unofficial information from well-informed sources among his comrades in Munich who, as early as 1912 have spread rumors that an attack by Czarist Russia is imminent.

Eisner, the internationalist, now changes his stance. Right up until the Balkan crisis, he had never wavered in denouncing the German Empire’s warmongering and its expansionist ambitions. Yet, in late July 1914, he issues a strong warning that “Czarism must be tamed through the unity of Europe’s civilized nations, then peace will be assured once and for all.”

Kurt Eisner considers himself to be on the side of the international labor movement. Like many leaders of the Socialist International prior to 1914, he supports national defensive war to protect the territorial status quo under international law. According to this view, a government is to be blamed for starting a war if it refuses to reach a settlement by arbitration.

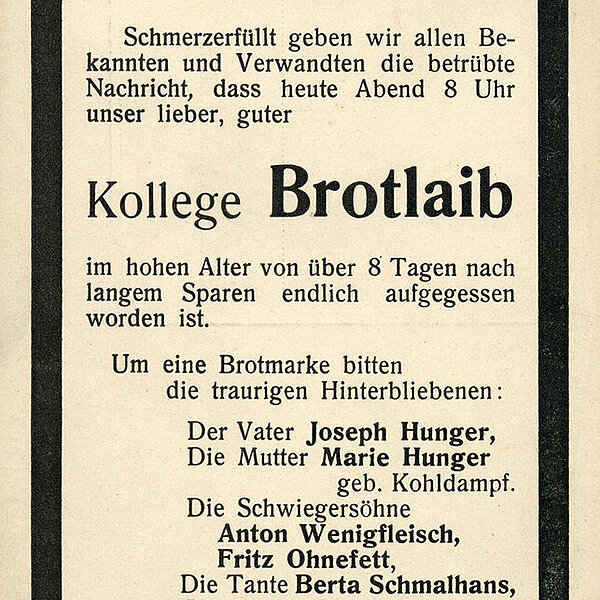

Nevertheless, he is dismayed by the burgeoning war propaganda and alarming rise in gung-ho patriotism that flourishes even within his own party.

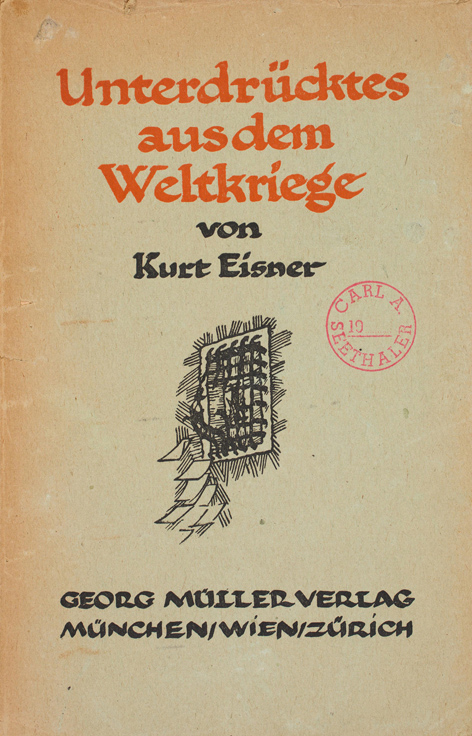

An increasingly skeptical Eisner studies the records. In August 1914, he learns of a telegram to the Imperial government that has been kept secret from the German public. Czar Nicholas II has proposed bringing the Austro-Serbian conflict before the Hague Peace Conference.

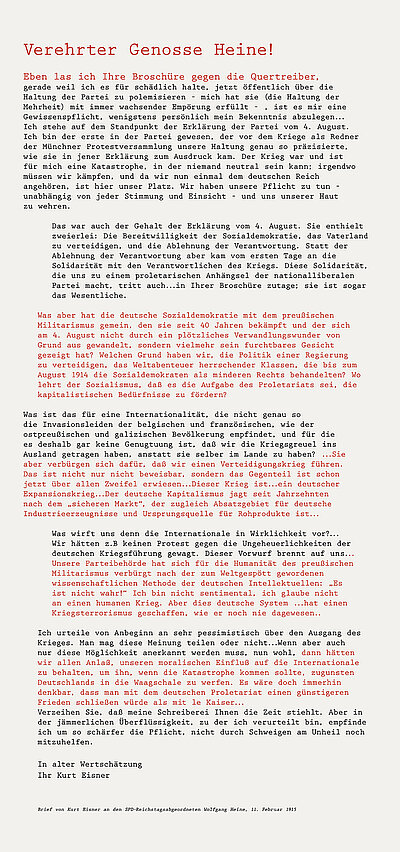

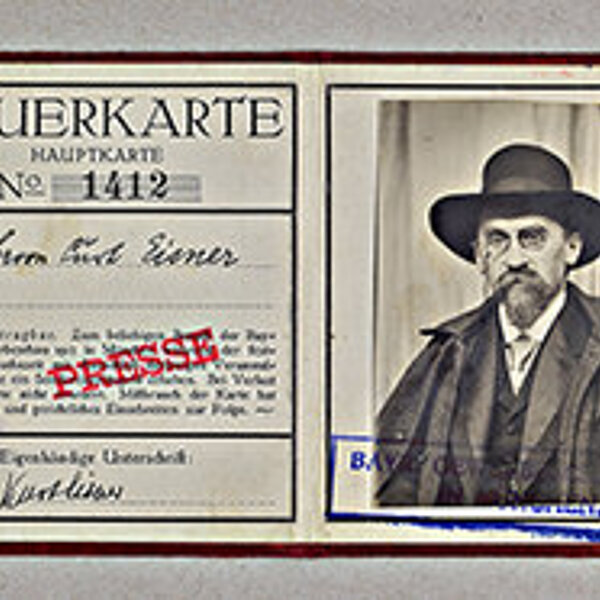

Eisner, the journalist, realizes that the blame for the war lies squarely with Germany. He follows his conscience and mounts a relentless information campaign against the German Reich’s policy. He becomes the driving force of the party-political opposition in Munich and a figure around whom the anti-war movement can unite.

He opposes Germany’s imperialist ambitions and sees the overthrow of the monarchy as a prerequisite to the initiation of peace negotiations.

In Eisner’s view as a socialist, to fight for peace is to fight for the revolution. The time has come for Kurt Eisner to assume the mantle of a revolutionary.

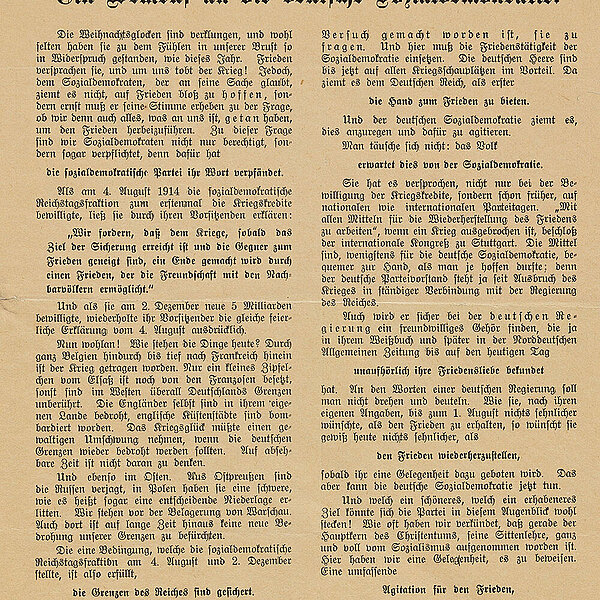

For Kurt Eisner, the Social Democratic Party neither can nor should share the war aims of the government of the German Reich.

However, the party leadership, most Reichstag deputies in Berlin and the state parliament deputies in Munich see things differently, as do the trade union leaders. Eisner’s change of heart that turns him into a staunch opponent of the war leads to a breakdown in relations with the majority of social democrats in Bavaria and Munich.

He is not yet ready to join the Berlin radicals. He is not attracted either by their revolutionary socialist wing led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg or by the more moderate opponents of the war who belong to the SPD’s Haase-Ledebour group.

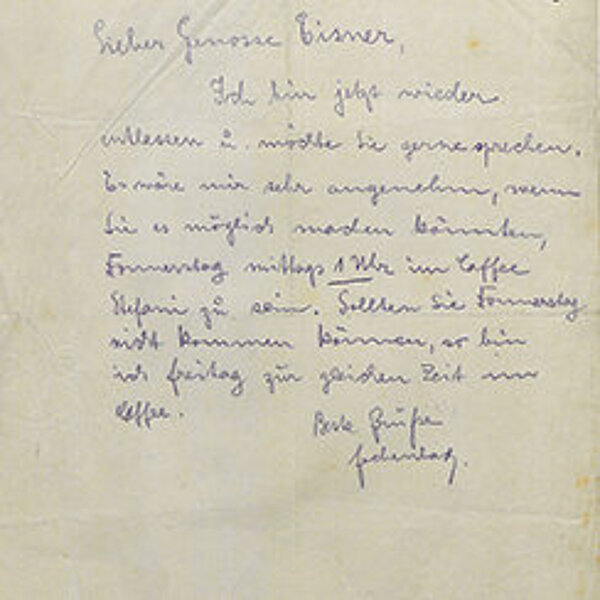

So Kurt Eisner writes a letter.

As a supporter of the anti-war movement, Eisner, within the SPD’s parliamentary group at the Reichstag, campaigns for making his party the party of peace. He supports the call for a return to the goals of the international labor movement.

In our organization, we have gradually brought things to the point where we have become a caricature of the Prussian state insofar as, while subjects may grumble about the government, we are nonetheless happy to leave everything in the government’s hands. When you hear comrades saying that party officials are nothing but scoundrels, then I put it to you that the blame lies not with those in power but with those who allow them to remain in power.

(Kurt Eisner on 7 January 1917, at the conference of the Social Democratic Working Group and the International Group)

Eisner first joins “Bund Neues Vaterland”, a pacifist organization, and then the “Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft” (German Peace Society).

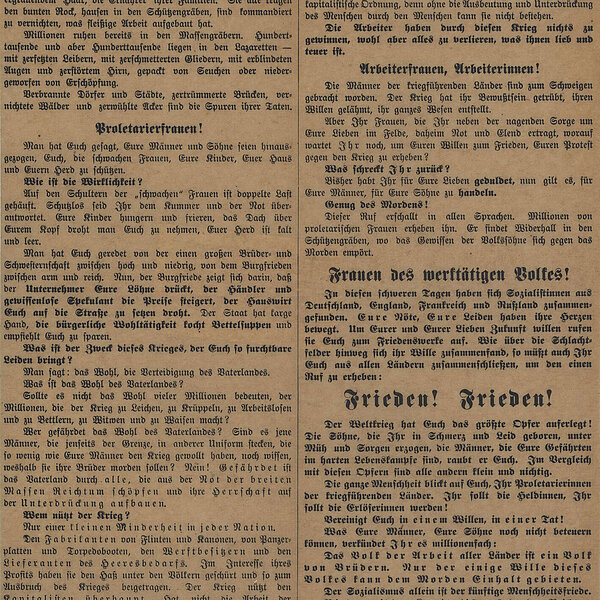

Here, he finds allies in the bourgeois anti-war movement and the women’s peace movement in his campaign to bring an immediate end to hostilities. He joins the “Münchner Friedensvereinigung” (Munich Peace Association) and makes the acquaintance of Ludwig Quidde, Lida Gustava Heymann and Anita Augspurg. At the same time, he attends meetings at “Bund Neues Vaterland” with committed pacifists such as Karl Liebknecht of the SPD and anarchist Gustav Landauer.

Kurt Eisner becomes a mentor and point of convergence for young socialists in Munich.

The Munich SPD youth wing comes out in opposition to the war. The young workers – including large numbers of wounded soldiers just home from the front – rebel against the diktats of the Social Democratic Party leadership. They don’t want the war, they never did. They want a different, a just, a democratic society built on international solidarity. And they are prepared to fight for it.

Kurt Eisner becomes the leading figure of this burgeoning youth movement as it strides towards revolution.

I wrote and put my shoulder to the wheel during the revolution

writes Oskar Maria Graf when recollecting his coming of age as a pacifist and non-card-carrying socialist.

But my book, written with all the carefree, quivering subjectivity of a rebellious thirty-year-old, was very different to all my subsequent works. It was by no means just an anti-war protest book. While I was writing it, it had grown without my even suspecting or willing it, into a comprehensive account of the extremely turbulent period between 1905 and the collapse of the 1918 revolution in Germany. And because it did not adopt the stance of a superior accuser, warner or admonisher who stands outside of their society, but portrayed a member of the anonymous masses still clearly part of that society openly confessing 'That is me too! I too share the blame for the catastrophe!', the youth of the day found that this book unintentionally spoke on their behalf.

(New York, USA, spring 1965. Oskar Maria Graf)

Plan Your Visit

Contact

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1

80331 München

Phone +49-(0)89-233-22370

Fax +49-(0)89-233-25033

E-Mail stadtmuseum(at)muenchen.de

E-Mail filmmuseum(at)muenchen.de

Ticket reservation Phone +49-(0)89-233-24150